![]() THE LAST BEST WEST: THE DANGERS

THE LAST BEST WEST: THE DANGERS

by B.B French

The last big timber fire within this area prior to the arrival of the new settlers was in 1885.. According to the senior Indians there had been a time that the entire area contained tall, lush forests. However, this fire jumped the river in one place and much good timber north of the Saskatchewan River was destroyed, as well as the topsoil between the moisture barriers, leaving only subsoil, wood and topsoil ashes for future growth of timber or homestead field crops. Poplars seemed to be best adapted to this damaged soil, and grew rapidly but did not replace the better timber. When the new settlers arrived there were the remains of spruce trees that were once 90 to 100 feet, that had toppled as the result of burnt soil at their roots.

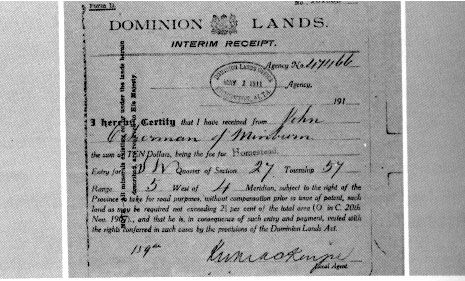

An example of the receipt issued to the homesteader for the ten dollar fee required as payment for the land.

In spite of the previous destructive timber fire, there was enough merchantable timber left to supply the rural and village settlers within a large area with millions of feet of lumber and thousands of squares of shingles. The Dominion Lands Office issued free timber permits to the settlers for building materials. Many people who lived on their homesteads during the winter, worked part-time logging and having their logs sawed into lumber at the local sawmills. Many sets of building logs were cut and thousands of tamarack fence posts were taken from swamps. Also a similar quantity of fence rails were cut for public as well as private use. Planed spruce lumber at that time sold for only $10. per thousand feet board measure.

Homestead years were years of hardship, and seldom did anyone escape the ordeal. Especially was this true of those who were forced to learn to speak a new language, learn the customs of the new country, and in some cases learn to farm. Some folks had always lived in towns or cities and were accustomed to many conveniences and found adjusting to their new environment rather difficult.

One bachelor relating his experiences to me about the years he had spent doing his homestead duties, ended his narration with, "Jesus Christ! Haven't I suffered!"

The second bachelor to complain after describing the slow progress he believed he had achieved while doing his homestead duties, remarked, "I believe the next time I homestead, it will be in the city!"

The third chap who narrated his experiences as we walked together for a distance of five miles, facing a twenty mile per hour wind and drifting snow with a temperature of 28 below zero, ended by saying, "I'm planning to leave here. Here I am almost twenty five years old; almost a quarter of a century old, and I haven't got anything yet!"

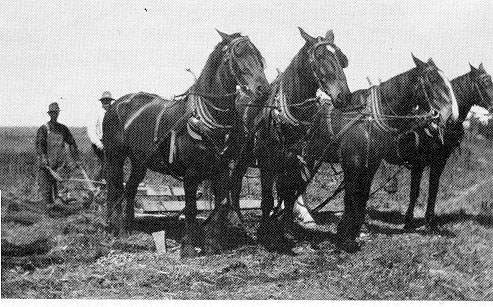

These three settlers, all good neighbors and good citizens, left their homesteads with the necessary improvements done to be eligible for their homestead Patent, and never returned. They had lost their time, labor, and money. They had gained an education by experience, such as, before being able to dig a water well at home, having to carry drinking water from a spring a mile away. They had experience in building construction - homestead style. They had done fencing, clearing of land the hard way with an axe, saw, brush hook, brush scythe, shovel, crowbar and mattock; bringing land under cultivation with horse and ox power. Sometimes they hired their breaking done or exchanged work with a neighbor who owned a team and plow. They did donation work on the road allowances and trails by making mudholes passable, installing culverts and small bridges made of logs and later logs and lumber. This experience and their state of good health was almost all the compensation they had for their effort and financial investment. There was no immediate known way of recovering any of it. Their successors benefited some by their labor, though there was no way of calculating these benefits. It was a case of an ill wind that blows no good.

Horses were used to bring land under cultivation

Approximately ninety percent of the earliest settlers were virtually forced to leave the area within a few years because of the isolation aspects, such as no roads, poor roads, and the nearest doctor and railroad town being from fifty to seventy miles from parts of the area. All the homesteaders did something on their land toward doing their homestead duties before leaving. However, a few returned after a number of years just to see what progress had been made during their absence, and to renew old friendships.